Samson Davis, the third of nine children of Samuel Davis & Betty Holbrook was born in 1818 at 4 Upper East Smithfield, Whitechapel in the East of London, at his fathers gunmaking premises.

He was baptised on Christmas Day in 1818 (along with seven other local children) at St Botolph Without Aldgate, East London. (baptisms were free on Christmas Day making it a very popular date).

Born into a middle class family, his father was a well known gunlock maker and inventor who patented three improvements to percussion cap gunlocks.

Unfortunately, in 1832, when Samson was just 13 years old, his parents died in the London Cholera epidemic within a week of each other. This left him and his only two surviving siblings John and Joseph to be raised by his paternal aunt Ann Keech (1783-1840) who was appointed guardian in his fathers will. Childless Ann was married to James Keech, a chemist from Deptford in Kent.

Samson’s younger brother John (born in 1821) immigrated to New York sometime before the age of 21, and his older brother Joseph (1807-1884) carried on his father’s gunmaking trade in East London.

At the age of 17 on 23 August 1835 Samson began his studies in medicine at London University College Hospital, and was then apprenticed for five years to a surgeon and apothecary in Kensington (Mr Robert Hesselwood of Sydney place, Commercial Rd, London).

As a young man Samson would have witnessed the ravages of disease and poverty surrounding him. It must have been unbearable to watch his own parents die of cholera within a week of each other when he was only 14 years old. Perhaps it was this event that spurred him to become a doctor.

From the age of 14, a boy was apprenticed to a qualified master for a term of 5-7 years. The boy lived in his masters house and undertook his apprenticeship without pay. His parents or guardians (in Samson’s case –his Aunt Ann) paid the master (Mr Hesselwood) a premium in a lump sum, which would cover tuition, board and lodging during the whole term of his indenture.

It was the premium that determined which occupation a boy could follow, or what his parents could afford. Since premiums were high for apprentice surgeons and apothecaries, this limited the class of boy who could enter this profession. By the 1800s, surgeons apprentice premiums had risen because the medical profession had increased in social status, as it was known that successful medical practices could be very profitable.

Medical apprenticeships were advertised in local newspapers. Sometimes the parent or guardian placed an advertisement themselves, searching for a master that would take on their son.

A young man in London interested in medical life during the early to mid 1800s had a couple of primary career paths open to him. He could apprentice with an apothecary and then eventually obtain a licence from the Society of Apothecaries, which would grant him the right to concoct medicines prescribed by physicians. After some training he would be free to embark on his own practice, treating patients with the woeful remedies of the day, probably dabbling in minor surgery or dentistry on the side. The more ambitious would go on to study at a medical school and later join the royal college of surgeons in England, becoming a bona vide general practitioner and surgeon, performing a host of different tasks: everything from treating minor colds to excising bunions to amputating limbs.

Within a few years Samson had obtained both his Apothecary and surgeon’s licence and established a practice at 19 Sidney Square, Stepney. Setting up shop as a doctor in those days required an entrepreneurial spirit. Competition was intense among London’s new medical middle class.

Samson entered University College Hospital in October 1839 and studied anatomy, physiology, botany and midwifery.

University College London England 1828

Medical classes also included operative surgery, nature and treatment of diseases, diseases of women and children, pharmacy, chemistry, medical jurisprudence, dissections and demonstrations, hospital and dispensary practice. A history of the University College Hospital is available here. Details of the courses, and the tutors are given in detail.

The foundation stone for the Medical Faculty of the College’s new hospital was laid in May 1833, so it was quite a new building Samson was attending, given he began attending in 1839. The name of the College was changed from London University to University College Hospital in 1837.

University College Hospital London

The first University of London degrees were initially examined for in 1839, following a two year course. A Punch cartoon of 1847 portrayed the medical students a curiosity for the wearing of their ‘costumes’ or medical gowns.

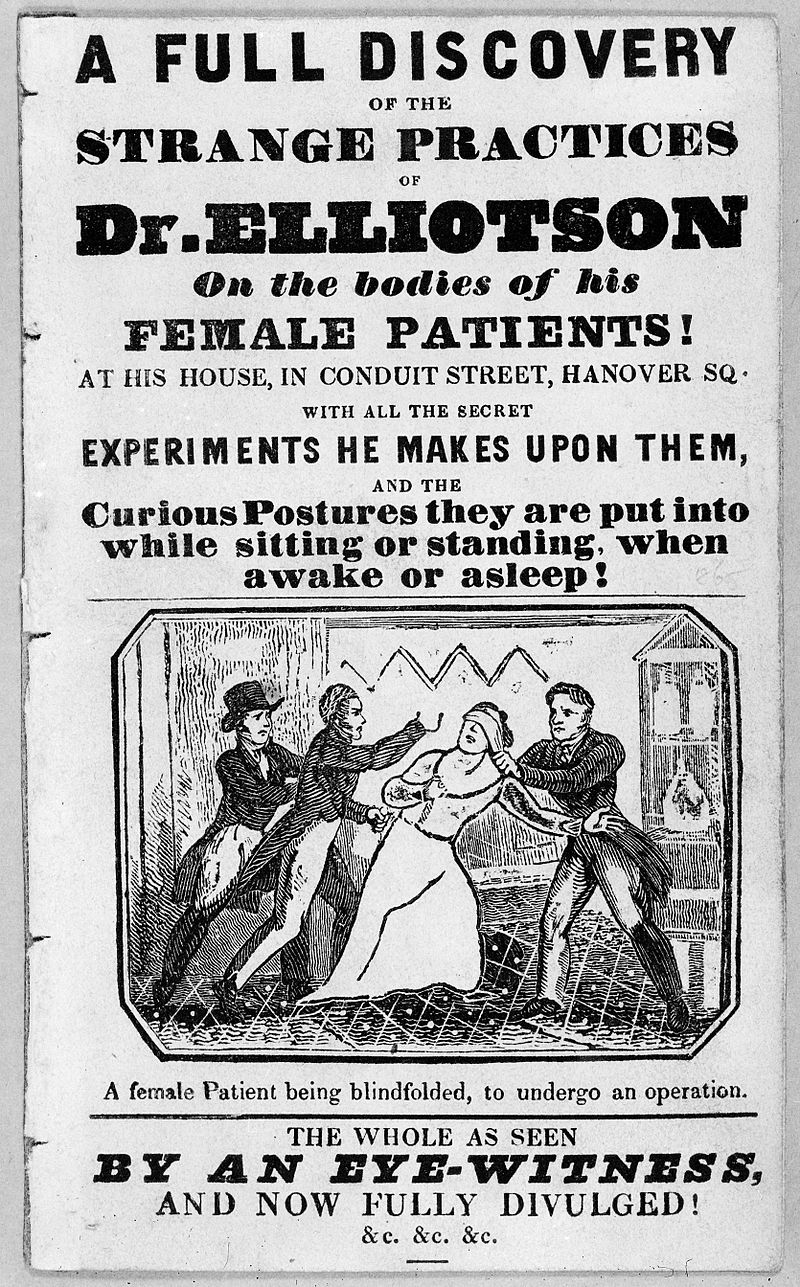

Anonymous anti-Elliotson pamphlet

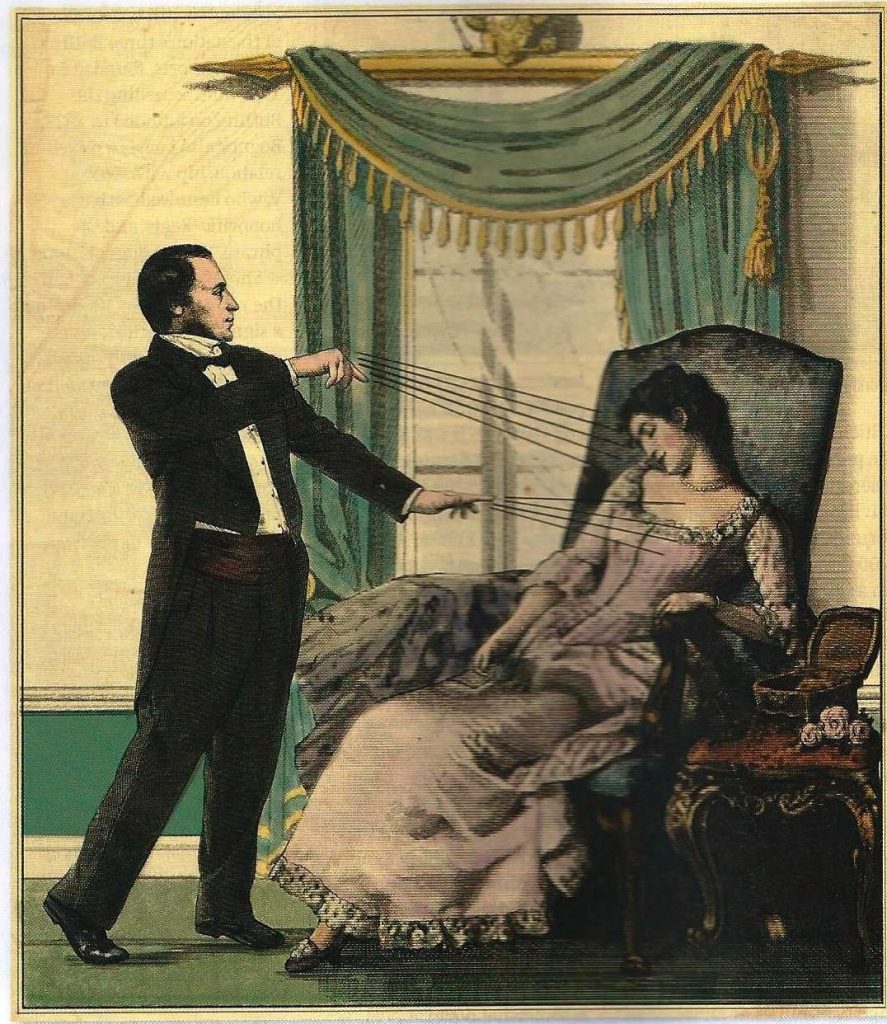

One of Samson’s tutors was involved in an early scandal arising from the Victorian craze for mesmerism. Dr John Elliotson pioneered the stethoscope and introduced the use of quinine for malaria.

Unfortunately he had to resign from the College when the medical journal the Lancet exposes two of his mesmerism trance patients, sisters Elizabeth and Jane Okey, as fakes.

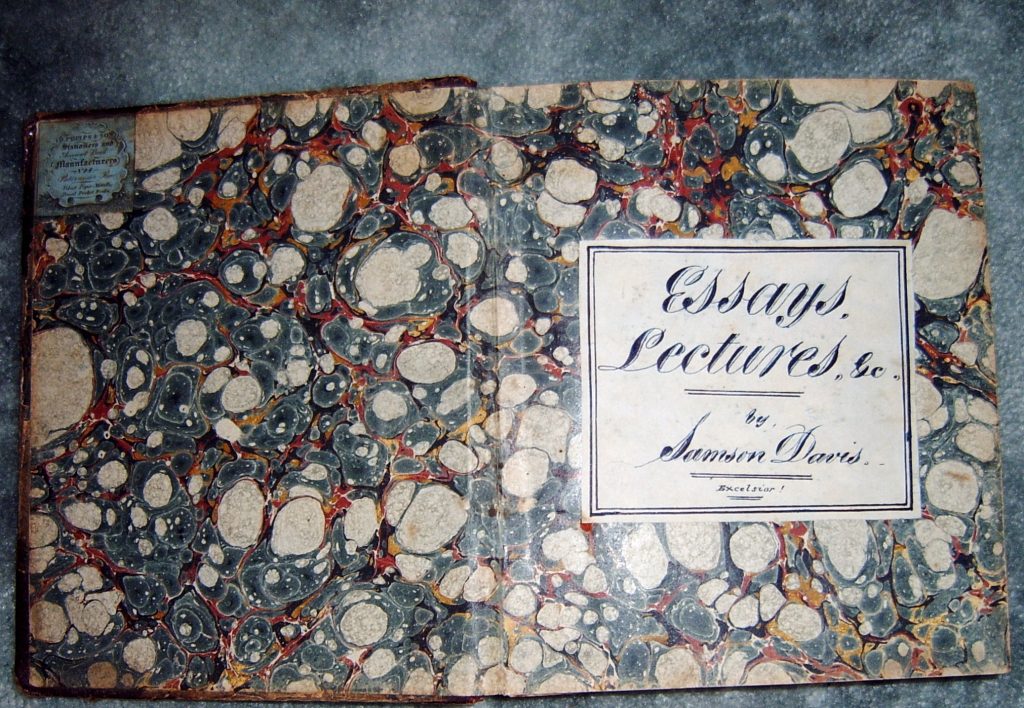

Samson also began giving lectures himself in London (Brentford) on mesmerism and hypnotism.

In the 1840s mesmerism was beginning to gain popularity as a form of pain relief in childbirth. Samson continued his lectures into mesmerism in Castlemaine, Australia.

The terms of his apprenticeship forbade marriage, so in August 1840 when his apprenticeship had concluded and he had attained the age of 21, he married Louisa Emerson (1814-1842), the daughter of a childhood neighbour and probable work colleague – George Emerson 1773-1838 and Elizabeth Leicester d 1842 (of 80 Upper East Smithfield).

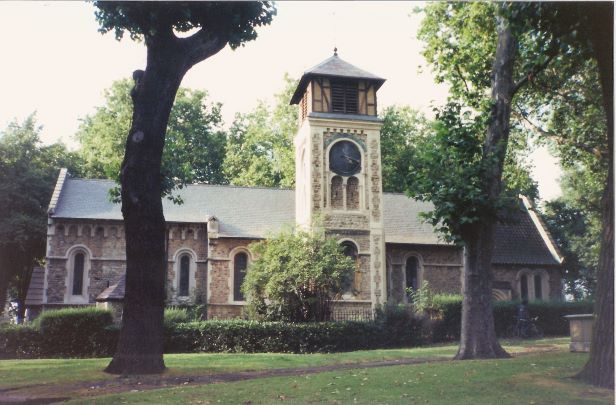

Samson and Louisa were married in St Pancreas Old Church in Camden and Samson was residing at Sidney Street, Mile End Road, Kensington at the time of their marriage.

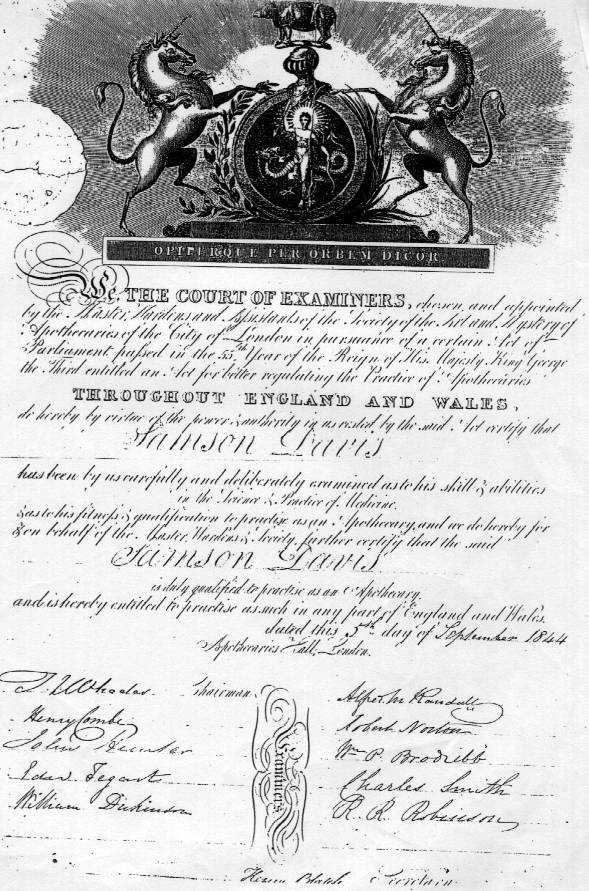

After examinations at University College Hospital he finally qualified as a fully licensed doctor and apothecary (LSA) on 5 Sept 1844.

The following year in May 1841 his wife Louisa gave birth to a daughter and they named her Louisa Leicester Davis, her middle name being Louisa’s mother’s maiden name. At the time of her birth they were living at 116 Tottenham Court Road in Pancreas, Middlesex.

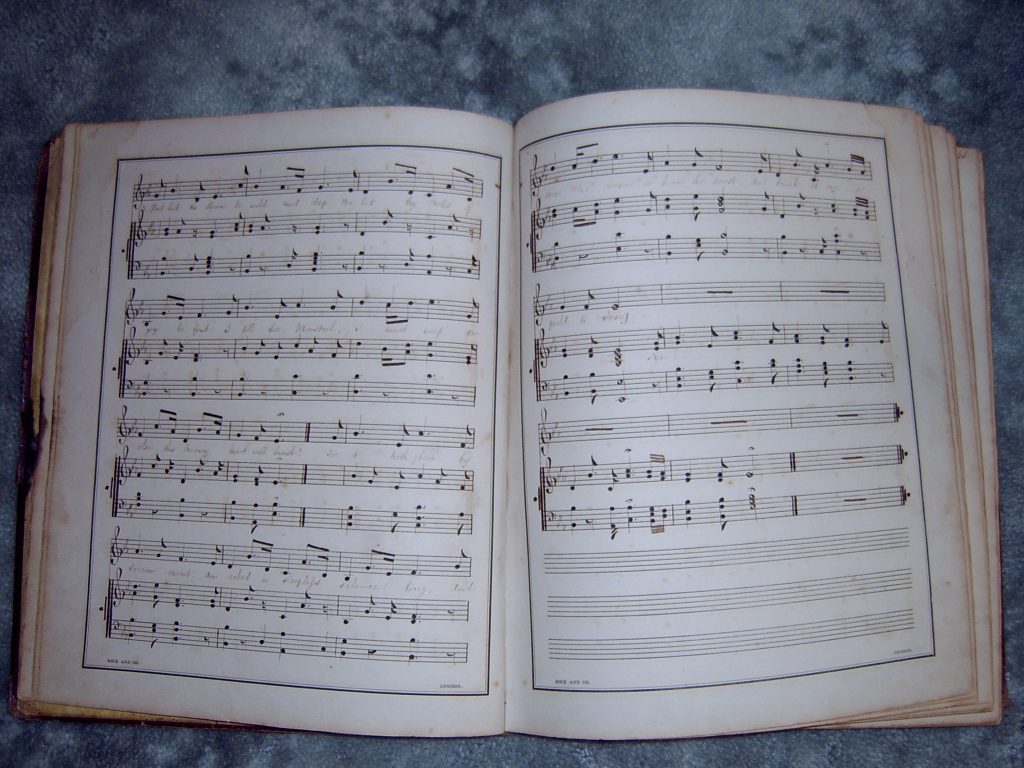

1841 must have been a happy year for the small family, with the addition of their first child, and Dr Samson started writing a book of music. ( I am lucky enough to have in my collection today).

Louisa came from a family of non-conformists, that is her parents did not practice the country’s national faith of Church of England. They were listed as protestant dissenters at her baptism.

Sadly the following year was a tragic one, starting first with the death of his nine month old daughter Louisa in March 1842, and then two months later the death of his beloved wife Louisa, aged only 28, to consumption (tuberculosis) in July. How sad for a doctor to watch his wife waste away, not being able to do anything. Louisa and their daughter were buried at St James, Westminster, Piccadilly. Samson was residing at 49 High Street Kensington with his brother in law, William Emerson a chemist at the time of Louisa’s death.

In September that year, in his great distress at the loss of his whole family, Samson decided to leave England and travel to New York and visit his brother John who was living there. We are very privileged to have his original diary of the visit. Samson travelled to the USA aboard the passenger ship “Independence”, and describes the voyage in great detail. Once again I am lucky enough to possess his diary penned at a most difficult time in his life.

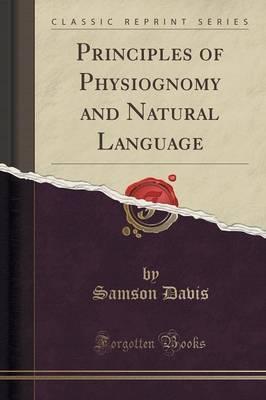

He returned to England sometime in 1843 and resumed his medical career, publishing a very well received medical book “Physiological Principles of Physiognomy and Natural Language”. (The book can be found online on Google Books and is still available as a  reprint on Amazon today).

reprint on Amazon today).

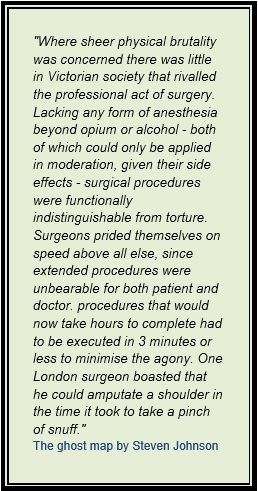

He was one of the first doctors to practise the art of mesmerism and hypnotism as pain relief in childbirth (remembering there was no other type of medicinal pain relief available for woman at the time).

Ann Reeves Rawbone / Rathbone

In the 1843 London Post Office Directory, Samson was listed as practising medicine and residing at 116 Tottenham Court Road, Marylebone, and this is where he met his second wife, 30 year old Annie Reeves Rawbone/Rathbone (1818-1860).

Ann was born in 1816 in Chalgrove, Oxfordshire and baptised there on 28 November 1816. She was the daughter of Thomas Rawbone and Mary Reeves.

Annie’s father Thomas Rawbone/Rathbone was the publican of the “Northumberland Arms” at 119 Tottenham Court Rd in the Northumberland Arms, where young Annie was working.

Samson married Oxfordshire born Annie on New Years Day 1846 in the church of the Holy Trinity in Brompton.

By now he was practising as a surgeon and apothecary (chemist), and lecturing around London on medical matters, as well as writing books and classical music.

He appears in the 1847-1849 London Medical Directory practising medicine at 19 Sydney Square, Mile End, London.

Samson and Annie had two children – George in 1849 in Mile End and Edward in 1851 while the family was living at 2 Palentine Place in the East end of London.

In 1852 Samson made a decision that would forever change his family’s lives.

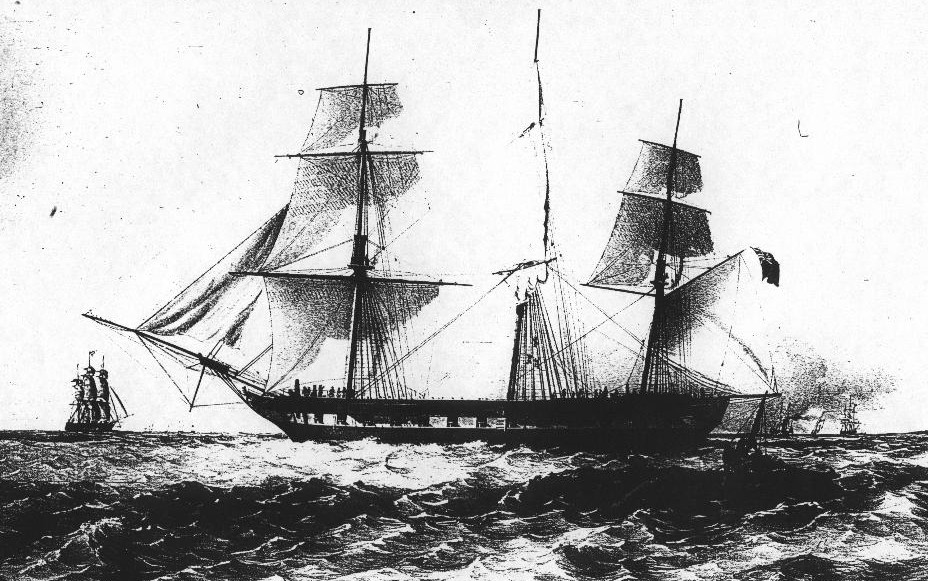

On 31 Aug 1852 he immigrated to Melbourne, Australia with his family aboard the ship “Gloriana”. His brother Joseph (and family) also came out that year aboard the ship “Marlborough”.

So why would Samson, a published author, with a successful medical career, decide to undertake a four month journey to the other side of the world to Australia? Was he running from something in the past, or was he a pioneer with hope in his heart for a better life?

Well, it seems it was all because of a situation involving Samson’s brother Joseph. Joseph was working as a gunlock maker in the Tower of London (like his father) and was contracted to the East India Company to make gunlocks. It seems brother Joseph needed to leave the country in a hurry to escape debtors prison, and must have persuaded his brother Samson to come with him.

In the company minutes of the Select Committee on Small Arms, May 1854, it states that Joseph Davis had “lately left for Australia under painful circumstances, having accepted bills to a large amount for a son of the late inspector, and not being able to meet them, he was obliged to abscond, leaving his debts unpaid.” That is – he hopped on board a ship and exited stage left to Australia. His brother Samson decided to pack up his wife and children, and do the same.

The London published Emigration Atlas of 1852 was printed to guide intending emigrants on the principal fields of emigration, including the route, distance, cost of passage to each place, and the class of labour to which they would be best suited.

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia is described as having a splendid harbour of Port Phillip with a population of 60,000. The land surrounding it was stated to possess all the qualities of New South Wales with a cooler climate, less subject to droughts, and ideal for the growth of wheat, maize and potatoes, unrivalled in any part of Australia.

The discovery of gold was likely to be a productive and permanent option in abundance providing great excitement. permission to work the gold is freely given by the local government on payment of a small fee to the Crown.

Upon arriving in Australia in 1852, Dr Samson Davis set up his medical practice in Market Street, Emerald Hill (South Melbourne), where his first daughter Mary Eliza was born in 1855.

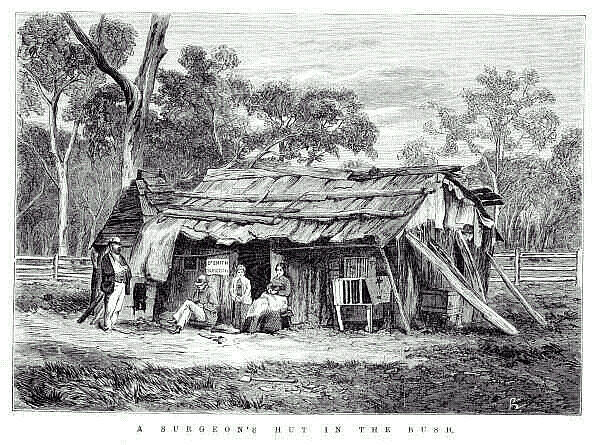

The colonial doctor lived and worked in a variety of environments. The city practitioner could rise to a considerable height on the social scale, and many acquired great wealth, occupying grand houses, employing servants, and travelling about in their own carriages pulled by beautifully-groomed horses. At the opposite extreme, the country practitioner often struggled to survive, travelling many miles on foot or by horseback to see patients.

Samson appeared to start off in great circumstances, living in a middle class area, and in London lived in a house with servants and fine things around him.

But out in Australia, things were very different.

He would have been responsible for delivering babies, attending accident cases, and treating every kind of illness that came his way. At this time treatments were extremely rudimentary, and largely directed at the symptoms rather than the causes of diseases (which were mostly unknown). He would have prescribed diet, exercise, enemas and leeches. Among the few medicines he would have had access to were quinine for malaria, digitalis for heart failure, colchicine for gout, and opiates for pain. His great enemy was infectious disease, and it was some years later before particular germs causing some of the worst diseases were identified, and then rational measures against infection, including vaccination (against smallpox), isolation, cleanliness and disinfectants, were implemented.

His surgery skills would have also been employed for minor amputations (fingers and toes), the excision of easily-accessible cancers, treatment of cysts, wound and bone breakage repairs, removal of diseased bone, and the occasional removal of kidney and gall stones. With little or virtually no anaesthetic available, it is no wonder he trained in the medical use of hypnotism to try to calm his patients.

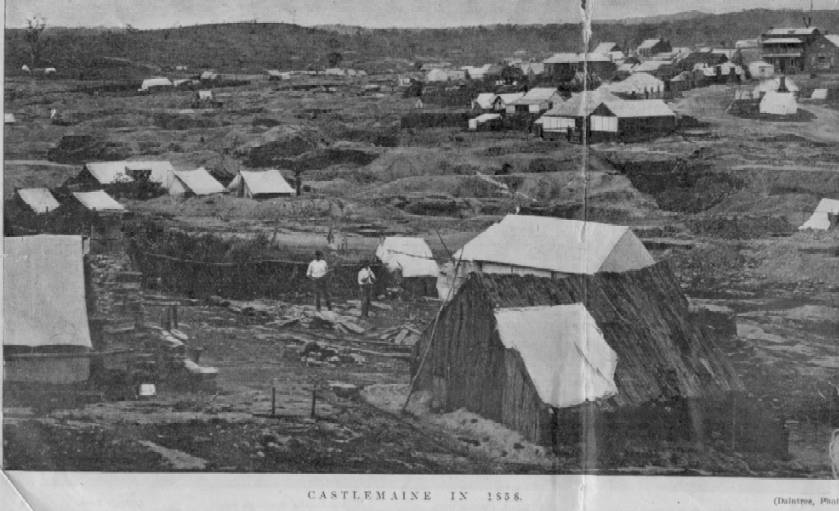

In 1856 he decided to leave the Melbourne environs and head 130 kms north west to the Victorian goldfields town of Castlemaine.

In September 1851 a shepherd discovered gold in a creek near his hut in Castlemaine. Within weeks some 3000 hopeful diggers settled in the valley to try their luck. The first land sales started in 1853 and several private residences were erected and Castlemaine was officially proclaimed a town.

In 1856 Samson’s brother Joseph (gunsmith) was appointed a member of the first Town Council. In 1862 the first steam train from Melbourne arrived in the town.

Samson set up his practise as a surgeon, apothecary (chemist) and accoucher in Barker Street, 4 doors from the Market Square. The following year in 1857 their last child Hardwicke Davis was born, but sadly died at the age of one month.

Castlemaine in the 1850s was a very rough, goldmining town with more tents than buildings. I can only try to imagine what going from society in London to living on the barren Australian goldfields would have been like. The rate books describe his property type in 1856 as a weatherboard cottage with a wood stove.

Samson is listed at a few different addresses in Castlemaine –

- 1856/57 – Parker Street, Medical Practitioner – Castlemaine Directory

- 1856/57 – Kennedy St, Castlemaine Surgeon – Vic Electoral Roll

- 1857 Alltmt 3, Section 1, Weatherboard cottage, 30 pounds

- 1857 Mt Alexander Mail Newspaper, Castlemaine, advert informing customers that Dr Davis, Surgeon and Accoucheur has removed from Barker St to Parker St

- 1858 – 59 listed on Legally Qualified Medical Practioners for Victoria.

- 1851-1860 small book “Maladies, Medicos and Miracle Cures – Guide to History of Medicine in Castlemaine” mentions Dr Samson Davis from 1851-1860, Parker St, Castlemaine.

- 1858 – Alltmt 17, Section 28, 9 Parker St, cottage and land, value 30 pounds.

From rate books it appears he also held on to his property in Market Street, South Melbourne (Emerald Hill as it was then known as), renting it out to several tenants. The property was described as being on the south side of the street, a wooden,dilapidated house with 2 rooms, the value being about 12 pounds.

In April 1857 he appeared in the newspaper as being nominated for town council and was appointed as a delegate in July to discuss the new Land Bill. In October 1858 he was receiving remuneration for being the Town Clerk.

He was still practising phrenology “observing and feeling the skull to determine an individual’s psychological attributes and mental traits”, advertising in the newspaper in 1857.

In 1858 Samson is mentioned in the Argus newspaper as lecturing on mesmerism in Castlemaine. It appears in his lectures he would invite an audience member up on stage and attempt to put them into a state of mesmeric sleep (a trance). The sceptical audiences see-sawed between boos, hisses and derisive laughter to being utterly astounded by the cataclysmic trance he was able to place some of the audience members into. You can read more about the use of hypnotism and memerism by Samson in article that I published about him here entitled ‘My mesmerising medical ancestor’.

The following year Samson moved his family to the nearby town of Newstead, and was elected as a polling officer for the election in 1859. Unfortunately he wasn’t going to live there for long.

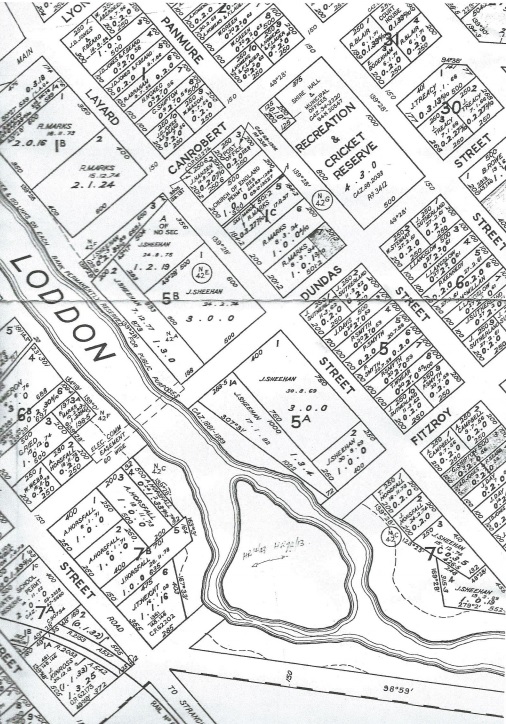

On 23 December 1860 Dr Samson was called out to visit a sick family across the swollen Loddon River and on his return drowned there, as the newspapers described in a state of ‘delirium tremens’ (drunkenness). A very sad end to a learned, and enterprising man. He was only 42 and left behind a wife and three children George aged 11, Edward aged 9 and Mary aged 5.

The Mount Alexander newspaper (Castlemaine) of 28 December 1860 contained a small death notice for him. Drowned accidentally at Newstead, surgeon, aged 42. Heavy drinker. Left wife & 1 child. Perhaps the two oldest children were already living with brother Joseph, a gunmaker, who later raised his sons George and Edward.

Sadly for our Victorian ancestors with a weakness for drink, temptation was everywhere. Their were beerhouses and hotels around every corner, and even grocers and confectioners were licensed to sell alcohol.

Habitual drunkenness was not just the problem of the drinker, since it destroyed their families, livelehoods and reputations too. Charles Dickens in his 1836 “Sketches by Boz” illustrated the problem thus –

“Drunkeness – that fierce rage for the slow, sure poison, that oversteps every other consideration; that casts aside wife, children, friends, happiness and station, and hurries its victims madly into degradation and death”

80 year old Ern Long who lived with his mother Irene and her father George Davis (son of Dr Samson Davis) for many years remembers George saying that his father drank to forget all the poverty and misery that he witnessed daily on the goldfields. He gave medical aid to the poor often without payment, and drank to get through each day.

Dr Samson Davis enjoyed a good life in London as a respected surgeon and apothecary (chemist), lecturing in prominent places, and authoring two books. He wrote music, and sermons, travelled widely (to America and then finally Australia), and was well known around London society and business circles. He had servants and possessions, so it must have been a shock to arrive from comfortable London to Castlemaine in the early 1850s which was virtually just a tent town.

But, who are we to judge? What a terrible hard life for a pioneer on the Victorian goldfields.

Samson was buried after Christmas on 28 Dec 1860 at Newstead Cemetery near Castlemaine in Victoria, sadly with no headstone to mark his final resting place. He left no will.

His wife Annie died of tuberculosis in Oxford Street, Collingwood on 15 February 1879 aged 63, and is buried in the General Melbourne Cemetery, with no headstone.

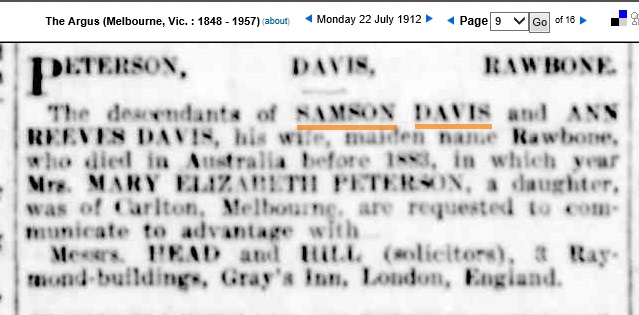

In 1912 a notice appeared in the Melbourne, Australian newspapers asking descendants of Dr Samson Davis and wife Annie to contact London solicitors, so perhaps there was money sitting in chancery awaiting them? Who knows if anyone in our family ever did find out!