Nicholas John Bolle was born in Dorstadt, Germany in 1836 to parents Heinrich (Johannes Heinrich Wilhelm) and Friederike Hartmann (Anne Marie Friedericke).

Nicholas was baptised on 31 August 1836 at the church of the Holy Cross, Dorstadt, Lower Saxony, Germany.

Heinrich (1791-1854) and Friederike (1792-1873) had eight children – Heinrich (1816-1873), Franz (b 1819), Elisabeth Louisa (1822-1897), Franziska (1825-1826), Maria (1827-1827), Antonious (1829-1832), Sophia (1832-1839) and Nicholas (1836-1899).

The youngest of eight children, he was born into a working family, his father’s occupation given as a ‘tagelohner’ (day labourer) and a ‘brinksitzer’ (a poor farm labourer who cultivated land at the edge of the village). So, was it poverty, and a chance to improve his fortunes that made him leave the security of his home, and lure him to the other side of the world?

Around the age of 20 he immigrated to Australia and made his way, most likely on foot, 150km in a northerly direction to the Bendigo goldfields. He would have followed a long line of fortune seekers.

Gold was first discovered in 1851 along the banks of the Bendigo Creek, and had resulted in a major goldrush to the area. Thousands of men from all over the world, eager to seek their fortune, flocked to the area. The Bendigo goldfields contained 37 different gold-bearing quartz reefs that extended across an area of about 16km. Between 1850 and 1900, Bendigo produced the most gold in the world. Today, the amount found would be worth around nine billion dollars. (Bendigo at the time was known as Sandhurst).

Rosanne Bolle nee Farrell

Somewhere along the way, 23 year old Nicholas met an Irish immigrant lass from County Wicklow, 20 year old Rosanna Farrell and they were married in December 1859 at St Kilian’s Roman Catholic church in the heart of the rapidly expanding city.

Rosanna Farrell was born in 1839 in Dublin, Ireland to parents Daniel Farrell (1807-1869) and Hannah Fox (1807-1877).

She was baptised on 29 July 1839 at St James catholic church in Dublin. Rosanna immigrated to Australia around 1858. Family story tells how Rosanna brought with her from Ireland a set of scales which she used to measure ingredients for the family’s cure all balm.

By 1859 (before she was married) Rosanna was expecting their first child, who they named Nicholas William Michael, and he was born at Ironstone Hill, a goldmining area in the Whipstick Forest, 15kms north of Bendigo in July 1860.

He was baptised at the age of two months in St Kilian’s in September 1860.

The church built of sandstone with a slate roof and completed in 1857, was a grand building with 22 buttresses and four entrances. Sadly however, only 30 years later, the building was condemned, and demolished. A new weatherboard cathedral built of oregon was built to replace it, opening for use in 1887. It is one of the largest wooden churches in the world and is still used today.

Refurbishment work was completed in 1982 and in 2002 the 150th anniversary of the church was celebrated.

Three of Nicholas’s children were also married in this church Agnes in 1890, Isabella in 1907 and Matilda in 1906.

Between 1860 and 1877 Nicholas and Rosanna produced nine children, all born in or close to the dense Whipstick Forest goldfields, just north of Bendigo. Every two years it seems they would make the 15km trek into the city to baptise their latest child at the largest catholic parish church in the district. Their birth certificates list the children’s birthplaces at the time –

1860 Nicholas, Ironstone Hill, Whipstick forest

1862 Agnes, Sandhurst

1864 Oswald, Scotchman’s Reef

1866 Henry, Whipstick Forest

1868 Rosanna, Eaglehawk

1870 Louisa, Eaglehawk

1872 Mathilda, Nerring (later known as Sailors Gully)

1874 Teresa, Nerring

1877 Isabella, Whipstick

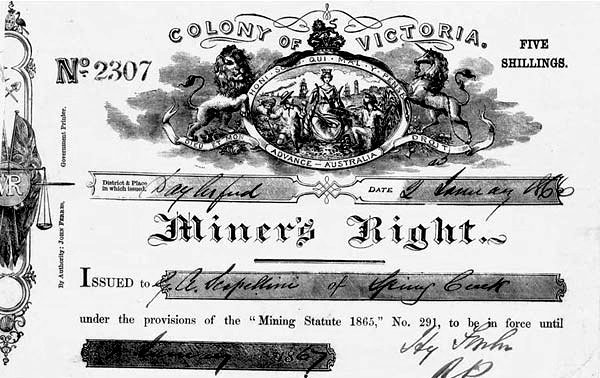

In March 1863 Nicholas registered his first mining claim, naming it Bolle’s Reef. Having worked this reef until it no longer paid, he went on a prospecting tour of the area and found another gold reef towards Elysian Flat, staked a claim and registered it under the name of his beloved wife ‘Rosanna’.

Sadly, as was often the case, the cost of hiring men to get the gold out of the ground, and removing it from the clay and quartz, outweighed the amount of profit he was making from his discoveries. In November 1863 while living and working at Old Tom Gully, Nicholas appeared in the Government Gazette as insolvent.

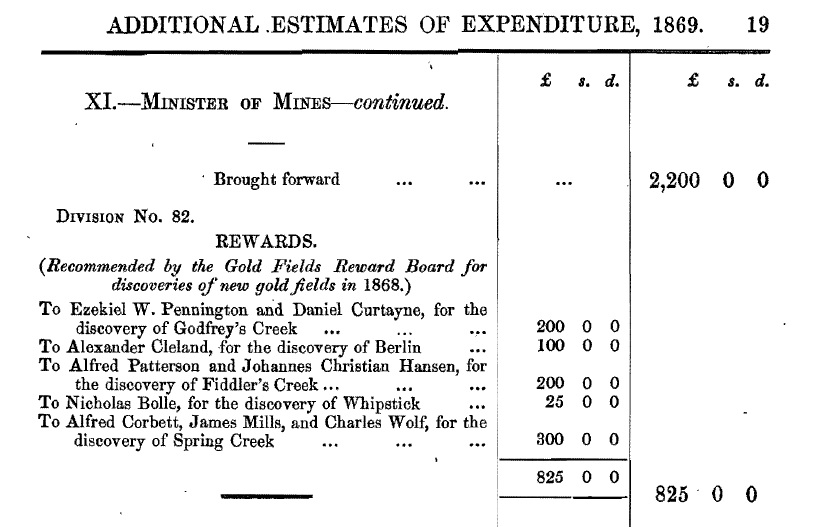

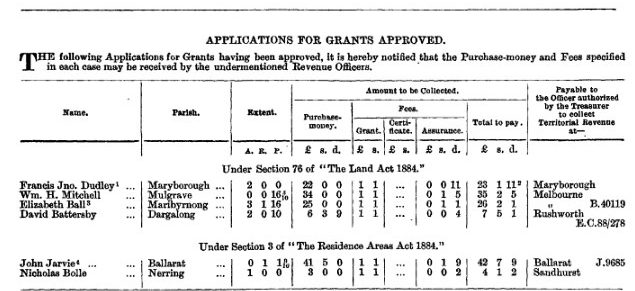

Nicholas continued to struggle on, scoping out the surrounding area in the Whipstick Forest, and having some little success and by 1869 he was given a government reward of 25 pounds for discovering a new area of gold in the Whipstick. The Government Gazette records this reward –

By 1872 Nicholas had established a quartz crushing plant at his mine in Old Tom Gully, a remote place in the middle of a heavily wooded ironbark forest.

Mining was a dangerous business, and in 1875 Nicholas was called as a witness in a coroner’s inquest into the death of a John Bashton who was accidentally killed in a mining accident at nearby Easter Claim in December. In 1881, he was again called to give evidence when one of his employees Mr Thomas Garrett was killed while working at his claim at Old Tom Reef. So we are fortunate to have Nicholas describing his day’s work in his own words.

The Whipstick

The Whipstick Forest (so named as the scrub was so dense, and the timber so high – whip like in form) was deemed almost impossible to penetrate in the 1862 edition of ‘The Victorian Goldfields’ by Sands & McDougall. It was described as “so thick, the traveller walking through it could not see a yard before him or around him, nothing but blue sky overhead. Water was scarce and uncertain to reach. Every step had to be cut through a dense undergrowth of creepers and rank vegetation. The compass was the only guide through it.”

The writer goes on to explain that he visited the mining camps in the forest and “came across a party of Germans at Jacobs Reef, working beside a small cottage, which was invisible at a distance of a dozen yards. An old man and an old woman and a little girl were busy fossicking for gold in a gravel heap. The area was guarded by dogs guarding it, and warning stragglers away.

Ten tones of stone had been taken from the ground by hand, and the yield was only a pennyweight of gold. The week before 89 ounces had been obtained from 21 tons of quartz. Five men could take out 20 tons in a fortnight of digging, and as wages of the hired men were 3 pound a week and the crushing and carting was done for 10s and 4 s, the owners of the claim had been fortunate, living on credit notes from the butcher and baker until they could pay.

Not far from Jacobs Reef was the one known as Unfortunate Bolle’s Reef, lately found by Germans, and the results of the first crushing. It was extraordinarily rich at first, but unfortunately it was only a patch, and was exhausted as soon as found.”

Many gold nuggets were found on the surface which attracted a flurry of miners to the area. In 1868 the local newspaper reported that a considerable quantity of coarse, shotty gold including several nuggets up to 30 ounces in size were unearthed at Bolle’s Flat, Whipstick.

In the Argus Newspaper (Melbourne, Victoria) on 13 June 1862 the headlines shouted “Great Discovery of Gold in the Whipstick” and went on to explain that a German man named Nicholas Bolle and an Englishman named Frederick Price, who had been working there sometime, but had never done more than kept their heads above water by dint of hard work, were the fortunate discovers. Nicholas was described as one of the earliest pioneers of the Whipstick, but disgusted with ill luck had tried other fields, but returned 18 months ago and struck stone just below the surface. The locality was visited recently, and Messrs Bolle and Price showed round among them the largest specimens, one half the size of a man’s hand which was valued at about 30 pounds. During the afternoon, someone pocketed this valuable piece. Later 16 pieces were exhibited at the Bank of Australasia in Sandhurst (Bendigo). Their total weight being 137 ounces of gold.

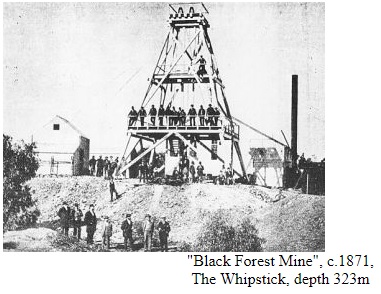

Nicholas operated a quartz crushing battery at Old Tom Mine. Many Whipstick reefs were very rich on the surface and to a shallow depth, but most were unpayable deeper. At first there were no crushing batteries and the cartage of quartz to Bendigo was costly for the early quartz prospectors. Later noisy crushing batteries were set up in the forest, pounding the quartz to sand and freeing the gold from its matrix.

Labourers dug out the quartz and carted it to the crushing battery. Then they shovelled it into the battery. They also carted wood for stoking the boilers, and to use as underground supports.

In 1862 the battery was described as a “primitive looking battery of from four to six stamps driven by a small high-pressure engine and worked by a party of Germans”. By this time a small settlement had developed around the area, dotted with neat permanent residences around Old Tom Gully.

In 1875 Nicholas described his day’s work while giving evidence at an inquest into the death of a man at the Easter Claim Mine, where he was a shareholder. He describes being lowered down underground via a windlass (with his 15-year-old son Nicholas) to a depth of 64 feet where they would work at digging out sandstone. The wooden props holding up the roof around him failed and John Bashton was killed. Mining accidents were unfortunately very common. Nicholas would eventually register these 13 separate mining claims –

1863 Bolle’s Reef (later known as ‘unfortunate Bolle’s Reef’)

1863 Rosanna, at Elys Flat

1863 Tyneside Co – 200 yards, Moores, Whipstick

1868 Bolle’s Claim – 75 x 65 Bolle’s Flat

1868 Whipstick Co – 200 yards Old Tom Gully

1869 Bolle & Co – 150 yards Nuggetty Whipstick

1871 Bolle & Co – 320 x 150, Easy Found

1871 Bohemian Reef – 150 x 150 on top of a hill, 1 mile east of Old Tom Gully

1875 Bolle’s – north side of Truck Gully, ½ mile north of the Camp Hotel

1876 South Easter – Easter Reef

1876 Derby – top of Sandfly Hill

1878 Bolle’s Reef – on the crown of Flagstaff Hill

1882 Old Tom Mine – quartz crushing machine and puddler

Nicholas appears in the Marong Rate books paying rates on property in the Eaglehawk and Nerring areas –

1866 Weatherboard cottage, Old Tom Gully – 8 pounds

1870 Hut – 12 pounds

1875 Splitter hut, Whipstick Forest – 4 pounds

1880 Cottage 8 pounds and Quartz Crushing Plant, Old Tom Gully – 50 pounds

1888 Nerring

1888 Eaglehawk

Nicholas appeared in the Eaglehawk Court of Petty Sessions three times over a number of years regarding goods sold, but defaulting on payment (1863), his pigs causing damage to his neighbours property (1869) and cutting down tree saplings without a license (1894).

In 1881, after almost 20 years working in very primitive conditions, in a remote bush location, Nicholas finally struck the gold had he had been searching for.

He was finally able to buy himself a piece of land at the Government Land Sales in the thriving gold town of Nerring (later called Sailors Gully) bordering the Whipstick Forest, in March 1888.

In 1896 Nicholas and Rosanna appeared in the local newspaper when they were involved in a buggy accident, both having been thrown out. Nicholas injured his arm, and their vehicle was smashed, but it appears they were not seriously hurt.

In 1899 applications were invited by the Sandhurst Prospecting Board for those that wanted to apply for prospecting financial assistance. Nicholas Bolle of Old Tom Reef made an application for a grant of 500 pounds for assistance to expand his crushing plant, thus allowing other miners to benefit from the use of it.

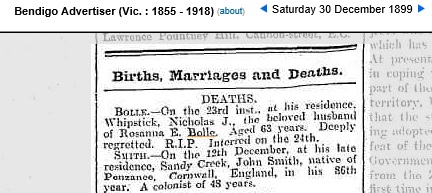

Nicholas died where he had spent most of his life in Australia, in the Whipstick Forest in December 1899, without making a will. His son Oswald, an engine driver also residing in the Whipstick was appointed the administrator of his estate in 1907, which consisted of 120 pounds worth of real estate, but no personal property.

Rosanna continued to live with her son Oswald in Sydney Flat, Whipstick and after suffering from a long and severe illness, most likely relating to her heart she eventually succumbed in November 1905.

Nicholas and Rosanne are buried with their son Henry in the Roman Catholic Section of the Eaglehawk cemetery, in an unmarked grave, surrounded by red bricks. (Section M, grave 201, interment no 6866).

A trip to the Whipstick

In March 2020, Brendan, the great, great, great grandson of Nicholas Bolle (1836-1899) and his wife Michelle (me!), decided to visit the Whipstick and see if we could still find evidence of Nicholas’s goldmining efforts.

We were amazed to find, despite the thick undergrowth, heavily wooded area, and remote location of the Whipstick Forest, there were still definitive traces of Nicholas and his family’s workings in the area.

I’ve explored many gold mine sites across the country, but never have I come across an area so well preserved, and sign posted and it was hard to believe, that this was all the work of Brendan’s ancestor Nicholas Bolle, and is still recorded on current day maps as “Bolle’s Reef”. Wonderful!

After driving through the old gold town of Eaglehawk on the outskirts of Bendigo, we passed the Camp Hotel which is still standing (mentioned in Nicholas’s mining claim of 1875) and arrived at Shadbolt’s Picnic Ground, the starting point for our walk through the Whipstick Forest.

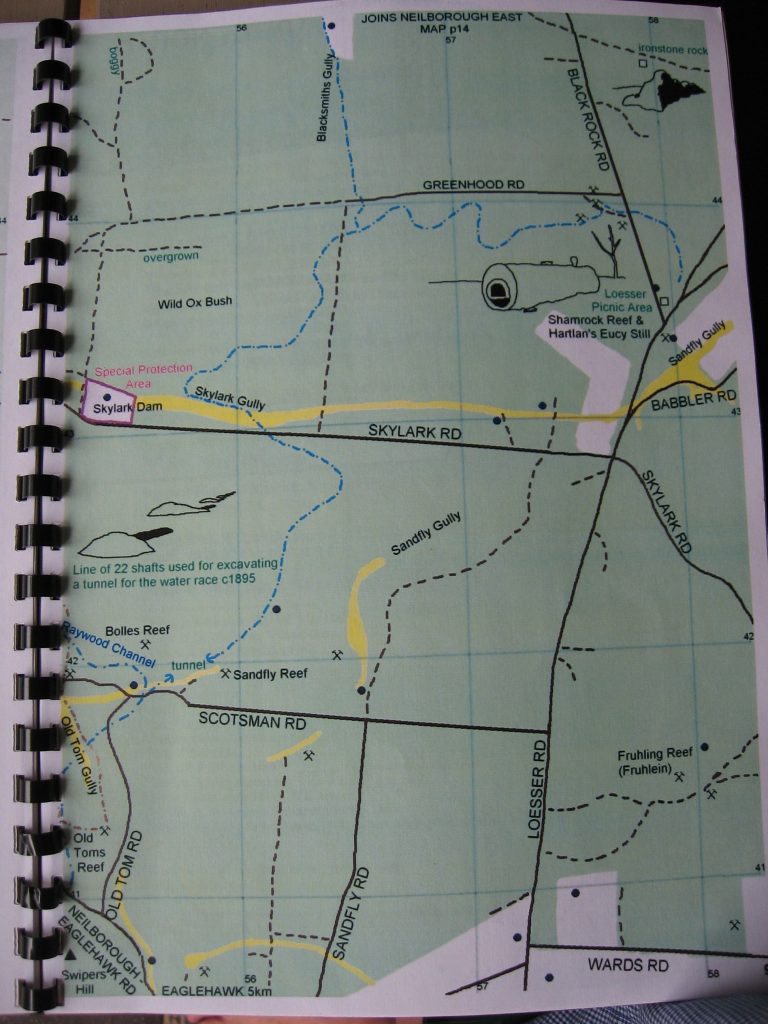

It was a warm Autumn day, and the air was alive with the sounds of birdlife, and the frogs could be heard croaking in the nearby pond. Armed with a basic (Greater Bendigo National Park visitor guide) map, we decided to tackle the walk through the ironbark forest to the Old Tom Mine site first, not knowing what we might discover.

Would there be any trace of Nicholas’s mining sites still visible over 150 years later in the middle of a dense forest?

All of Nicholas’s mining claims were in about a 10km square area, and fortunately for us, three of them (Flagstaff Hill, Bolle’s Reef and Old Tom Mine) can be reached by marked walking trails, which all start from Shadbolt’s Picnic Area, which is situated at 925 Eaglehawk-Neilborough Road, Woodvale.

It didn’t take long before we came across an amazing long water race, dug by hand, and lined with clay called the Raywood Channel.

Miners constructed earthen water races following the contours of the landscape to carry water across gullies and through gold working areas.

Miners working in groups of 8 to 10 would then wash gold from dirt in timber boxes using water from these long races. This allowed the miners to continue their work, even when nearby creek beds dried up.

The whole ground area was littered with dazzling pieces of white quartz, of various shapes and sizes. Some tinged with pink, or veined with black.

We could well imagine all the quartz that needed to be carted to the crushing battery and broken up to extract the gold.

We were careful to stay on the marked track, as on either side were many old mine shafts, long since abandoned.

After trekking a few kilometres through the bush, brushing away the huge buzzing march flies, and following our vague map, we finally came across what we had been hoping to find – the site of Old Tom Mine, where Nicholas and his troop of employees worked and had his quartz crushing battery.

We know Nicholas had been living and working here from 1868 when he registered his first claim in the area, and I suspect this is the area he died in 1889.

-

Old Tom Mine -

evidence of shaft -

open mining shaft

Our next discovery was even more exciting – the remains of the Puddling Machine used by Nicholas and his men at the site. Although difficult to see in the photos, it was clearly distinguishable and in fact has been granted heritage status by the City of Greater Bendigo as one of the few remaining puddling sites in Victoria.

The puddling site is very rare in that the trench still has traces of its timber lining. The site is a good characteristic example of the puddling technology developed in Victoria from 1854 in response to the need to process enormous amounts of clay soil which needed to be broken up to get at the gold.

Horses were used to drag harrows around a circular ditch in which the soil and water were mixed. The wooden post can still be seen in the centre of this circle.

The Old Tom Reef Gold Puddling Site is historically and scientifically important as a characteristic and well preserved example of a site associated with the earliest forms of gold mining which, from 1851, played a pivotal role in the development of Victoria.

Puddling machine technology is particularly important in the history of Victorian gold mining as the only technology or method developed entirely on Victorian goldfields.

Clay deposits scattered right around the area of the Old Tom Mine. Clay was carted to the puddling machine and broken up to extract the gold.

Then it was time to return to the start of our walk, and try to find the site of one of Nicholas’s other known mining sites at nearby Flagstaff Hill.

We know from mining records that Nicholas registered a claim on ‘the crown of Flagstaff Hill’ in 1878 calling it ‘Bolle’s Reef’.

Flagstaff Hill, Whipstick

After a steep walk uphill, we were rewarded in wonderful 360 degree views from the top of a lookout tower that has been built right on top of Flagstaff Hill. Nicholas certainly picked a great viewing spot for his mining site.

Described in 1862 as the highest point in the Whipstick from which an extensive view of the surrounding scenery is obtained. It is a vast mass of quartz with little gullies at its feet, where diggers work.

-

Flagstaff Hill Lookout -

Flagstaff Hill

The site of Nicholas’s 1878 gold mine on the crown of Flagstaff Hill, Whipstick Forest

SOURCES

- History of St Kilian’s, Bendigo – Catholic Diocese of Sandhurst website

- Mining claims and map, Bendigo Family History Society

- Victorian birth certificates

- Victorian Government Gazette 1869

- Coroners Inquest, Victorian Public Record Office

- Bendigo Independent Newspaper, Mon May 1, 1896 (Buggy accident)

- The Argus Newspaper, Fri 13 June 1862

- Bendigo Advertiser Newspaper, Dec 8 1875

- Remembrance Parks Central Victoria, Eaglehawk Cemetery

- The Goldfields of Victoria in 1862, Sands & McDougall, Melbourne 1863

- Victorian Heritage Database, Heritage Council of Victoria

- Tales of the Whipstick by William Perry

- Bendigo The German Chapter by Frank Cusack, German Heritage Society (own copy)

- Life, Death and Gold in the Whipstick by Ian Belmont

- German Claim Holders, Register of Mining Claims, Sandhurst Mining District, Public Records Office of Victoria