Susanna Mill, (Susan Mills, Shusan Milne), was born on 7 March 1815 in Bogfur, near Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

Bogfur, Aberdeenshire

Susan was baptised on 17 March 1815 four miles from her birthplace in Kintore, Aberdeenshire to parents George Milne 1781-1864 and Helen Shand 1782-1838.

Susan’s baptism was difficult to find, but it was finally unearthed under the old Scottish language version of her name ‘Shusan Milne’. This Milne family have been confirmed by DNA research.

Susan’s father George was a farmer at Bogfur, and also an elder in the Kintore Kirk (church) from 1831. Bogfur is also described as in the area of Kemnay and Inverurie.

Susan’s mother Helen died in April 1838 after having eight children. Kintore is 12 miles from Aberdeen.

It is unknown when or why Susan left her home in Kintore.

Perth, Perthshire, Scotland

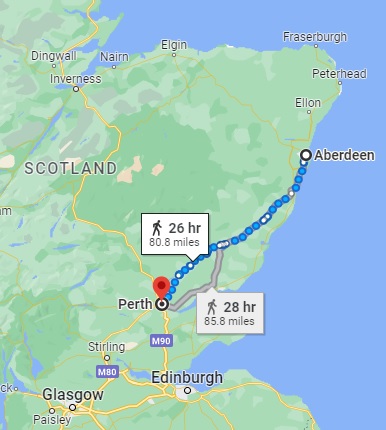

Around 1833, when she was aged about 18, Susan had moved 83 miles south down the coast to the city of Perth, Perthshire, Scotland, perhaps to other family, perhaps to escape someone, or maybe to find better work opportunities, but she soon found herself in trouble with the law.

Susan was one of many girls with no obvious family support, desperate and living in dire poverty. There was no social welfare or safety net, and the only other alternative to stealing or making money by other means, would be to face the appalling conditions of the workhouse. She appeared to be one of many similar poverty stricken girls, struggling to feed and clothe herself, and eventually resorted to petty theft.

In September 1835 Susan was convicted and sentenced to three months in prison for stealing ale from a cellar with some others (James Ross, James & wife Mary Scott) in Canal Street, Perth. Her trial was held at the High Court in Perth on 12 November 1835 and she was convicted of theft (stealing from a person) and aggravated house breaking. (National Records of Scotland Ref JC26/1835).

A detailed description of the Perth County Jail in 1819 (Gurney) exists –

The Perth County Jail in 1819 was a new stone built building. There are separate buildings for male and female prisoners. The buildings are lamentably inadequate. On the women’s side, there are four small rooms with a fire place and a good bed for two persons in each of them. There is no classification of prisoners and several children are with their mothers. One child has small-pox. There is an infirmary but the children are not placed there. The prisoners are allowed a little clothing occasionally and are obliged to wash themselves every morning. There is no place of worship which seems strange in a religious society such as Scotland.

A prison was constructed at the rear of the County Buildings in Perth (the venue of High Court Trials) by 1823. A passage was created from the prison cells to the witness stand and dock. This prison had two separate blocks for male and female prisoners.

The Scotland Criminal Index on Ancestry states that Susanna Mill was aged 21 years, born in 1815, residing in South Street Perth, and committed the crime at Fleshers Vennel in Perth. (Scotland High Court Criminal Indexes 1790-1919, Ancestry).

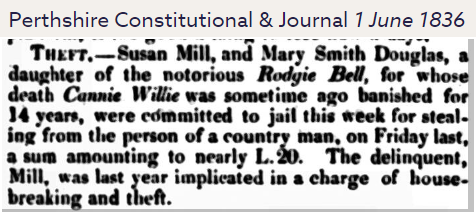

The following year on 1 June 1836 Susan Mill was in trouble again with a Mary Douglas for stealing –

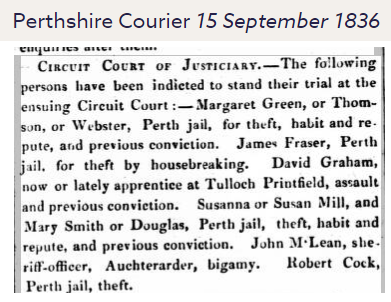

She was indicted to stand trial at the ensuing circuit court.

Females with no skills or money, and who had no male family or protector, had very limited choices in regards to making money to survive. Many only had their bodies to sell, with the aim to get their customers drunk and rob them (called ‘bilking’). Prostitution was not the end game, just a means and a cover for thefts from a person. Those that had other family members to support them were better off (group survival) but those that struggled alone walked a line between survival and petty crime, often resorting to alcohol and stealing to temporarily relieve their poverty.

Susanna’s trial is not a pretty read, and it seems she had been known by Sergeant of Police David Low to be living in Perth for 2-3 years previous to her conviction. The two girls Susanna Mill (alias Susan Mills) and Mary Smith or Douglas were trying to make money on the street, and stole a pocket book from a 36 year old farmer Mr George Butchart in a room in a pub in the area of Fleshers Vennel in Perth. The publican gave evidence against the girls, whom he seems to have recognised.

Constable Thomas Anderson, residing in South street, Perth aged 49, agreed with Sergeant Low, and remarked that he has considered Mary Smith a common thief for some years past, but he cannot say that Mill is a common thief, as she has not been long in Perth, and by living in the suburbs, did not come so much under his observation, but she “does nothing to obtain a livelihood by industry”.

Susan herself gives quite a clear testimony on her own behalf, and states she is 21 years old and resides in South Street, Perth. She admitted that she had twice been tried and convicted of the crime of theft before the sheriff of Perthshire, and once before the Police court, and she declares that she cannot write. She protests her innocence but it is clear that Susan and Mary were both in the room with George Butchart, and it seems they did try to take the money from his pocket book. The girls both plead guilty to the charges. (National Archives of Scotland AD 14/36/69; JC 11/84/19)

Note – there is an entry in the National Records of Scotland catalogue for a Susan Mill appointing a curator bonis (guardian) and then removing it. This is for a different woman, that of a wealthy woman in Dundee Scotland who was placed in an asylum for a year.(National Records of Scotland CS44/181/25). Full copy obtained.

Indictment

Susan and her friend Mary were then charged with stealing sixteen pounds sterling or thereby in bank or bankers’ notes, and a pocket-book, from George Butchart on 30th May 1836 in the public house kept by James Robertson.

Prior convictions for theft:

• Susan Mill – 6th November 1835

• Mary Smith – 5th January 1831, 5th March 1831; 16th June 1834

(National Archives of Scotland AD 14/36/69; JC 11/84/19)

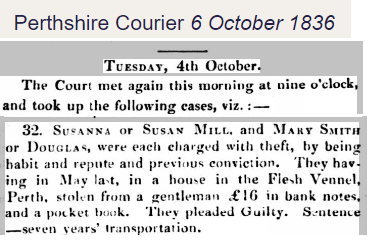

SUSANNA or SUSAN MILL, and MARY SMITH or DOUGLAS, Perth, charged with stealing in May last, from the person of George Butchart, farmer, Lumbenny, in the house of James Robertson, Flesh-Vennel, Perth, the sum of £16 sterling, and a pocket book, and with being previously convicted of theft, and being habit and repute, pled Guilty, and were sentenced to 7 years’ transportation. Perth Advertiser, 6 October 1836.

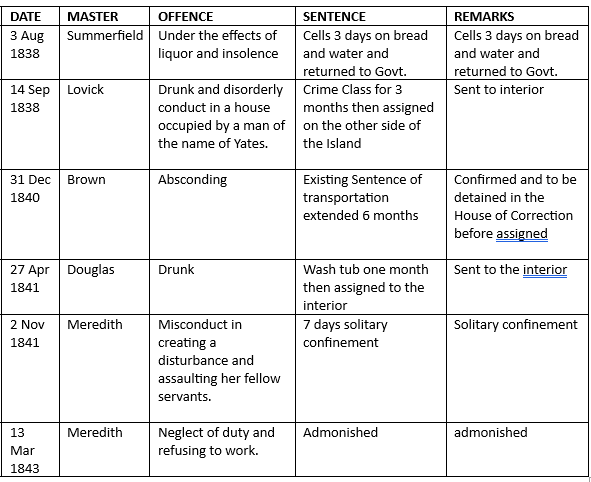

Susan was transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) on the convict transport ship ‘Atwick’ departing Britain on 28 September 1837. Her occupation was given as a laundress.

13,339 female convicts in total were sent to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), and 68% of these were transported for seven years, as Susan was. Some 779 were sent out for life sentences, and 286 of those had been commuted from the death sentence. Mostly those that did receive the death sentence were for murder, infanticide (killing ones own child) or rape (or kidnapping or luring someone to be raped by someone else).

It appears about 6% of all female convicts that were sent to Tasmania received a life sentence, and these were mostly women aged 20-29 years, as Susan was. The majority of crimes committed by the convict women were larceny, robbery, housebreaking, burglary and stealing by servant.

From studies taken it seems that your native place of birth and the trial county you were tried in had a significant bearing on the harshness of your criminal sentence. Fortunately for Susan, Perth in Scotland had a much better outcome, particularly for females, than for example London. In another part of the British Isles, she may have received the death penalty for her crime. It also seems that the introduction of harsher penal laws over the years were the main contributing factor on whether a convict would be issued with a life sentence.

In 1723 an Act of Parliament called the Black Act, introduced the death penalty for a large number of capital crimes. It was expanded over the years to include over 350 crimes for which attracted the death penalty. Some of the crimes included poaching, arson, cutting down trees, vandalising private gardens, forgery, stealing goods worth a shilling and even being unmarried and concealing a stillborn child. Local villagers could be punished if they failed to find, prosecute and convict alleged criminals.

Wealthy landowners that had the ear of parliamentary lawmakers were always trying to protect their properties from the poor (poaching, gleaning, etc) and push for harsher penalties. The government was always fearful of the poor revolting against them or causing unrest, and as a result petty crimes became felonies and capital offences. A criminal law reform campaign in the early 19th century caused it to be largely repealed on 8 July 1823, when a reform bill introduced by Robert Peel came into force.

Very fortunately Susan escaped capital punishment for her crime, and was sentenced to seven years transportation beyond the seas, which in her case meant Van Diemen’s Land, or Tasmania. Women convicts were not placed in prison hulks on the water like the men, but were detained in land prisons, and then sent aboard the convict ships, ready to depart England forever.

Old Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land

The “Atwick” Convict Ship

The ‘Atwick’ contained 151 passengers (the rest crew), arriving on 23rd January 1838 in Van Diemen’s Land. The average sentence of the convicts was 7 years, with 5 life sentences given. There were 151 convicts, 18 convict children, 5 free women and 9 free children travelling aboard. Just one death and one birth occurred on the voyage, making the total number of 181 people that arrived the same as the number that left Woolwich, Kent.

The Surgeon-Superintendents report tells us that the general condition of the convicts onboard was favourable. The prison was opened at sunrise, the bedding brought on deck, shaken and stored, and each prisoner was mustered to wash her person.

The Surgeon-Superintendents report tells us that the general condition of the convicts onboard was favourable. The prison was opened at sunrise, the bedding brought on deck, shaken and stored, and each prisoner was mustered to wash her person.

Convicts that could not read or write, such as Susan, were engaged at school with the better educated convicts teaching the others. The others were employed at needlework.

The prison deck, water closets, and hospital were sprinkled with chloride of lime three

times a week generally at night after prisoners had returned to bed – as a means of fumigation. P Leonard, surgeon Superintendent report that with the exception of the two individuals affected with rheumatism and ophthalmia who were sent to Hospital in Hobart Town, all were landed in excellent health.

The General Remarks section at the end of the surgeon’s journal gives an excellent description of how prisoners were organised aboard the ship. Their daily routine, meals times, bathing, schooling and measures to prevent scurvy are set out. Most interesting is the mention of dancing and other light entertainment to maintain health through excercise. The surgeon Peter Leonard, undertook four voyages on convict transport ships, delivering over 800 mostly male convicts with only six deaths overall – a very impressive record. Female Convicts Research Centre Atwick General Remarks.

29% of the ‘Atwick’ female convicts in 1838 were said to have been charged with ‘on the town’ (prostitution and vagrancy), and only 15 of the 78 Scottish convicts could sign their name. Susan appears on the Atwick’s passenger list in the book “Abandoned Women, Scottish Convicts Exiled Beyond the Seas” by Lucy Frost.

On Susan’s Convict Description Lists she is described as a housemaid, height 5 ft 2 3/4″, age 22, sallow complexion, oval head, light brown hair, round visage, low forehead, light brown eyebrows, grey eyes, medium nose, medium mouth and chin from Aberdeen. (CON40 & CON19).

Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land

When the women landed in Hobart, the early convicts were mostly assigned out to free settlers with the promise of reliable food, clothing and shelter, but before that happened they entered the probation system.

Later on the Probation System was introduced in Van Diemen’s Land for female convicts in 1843–1844, a few years after it was introduced for men. Instead of being assigned on arrival to work for settlers, a female convict served a term of probation (the length depending on her sentence), during which she was given moral and religious instruction, and taught domestic skills as required for cooks, laundresses, and servants. At first convicts spent the probation term on the hulk Anson and, after its disbandment, at the New Town farm station.

The length of time in the probation program depended on the convict’s original sentence and her behaviour in the program (but usually a mandatory minimum period of 6 months). The probationary period could be extended for bad behaviour during this period with or without other punishments (e.g. hard labour, solitary confinement).

After serving her term of probation and in theory at least being ‘reformed’, a female convict worked for a master or mistress as a passholder. After a period she could apply for a ticket of leave, then a conditional pardon. Source: Female Convicts Research Centre Inc.

Given that Susan arrived well before 1843, she wasn’t subject to the Probation System, and would have been assigned straight away after arriving in Tasmania to a master (or mistress) as a domestic servant.

If all went well, they remained with that master. In fact some female convicts remained with the one master for their entire sentence. But if they committed an offence the master or mistress considered serious, such as insolence, neglect of work, getting drunk or being absent without leave, they were taken before a magistrate and tried. (It seems Susan was charged with nearly all these offences!). They were then either acquitted, admonished or punished by being sent to a female factory and either serving a term in Crime Class or serving a sentence in solitary, sometimes on bread and water.

Many female convicts on assignment learnt domestic skills which were useful to them in later life, either earning a living or running their own homes. However, without the protection of their family and with little protection by the state, they were also vulnerable to abuse, mental or physical. Many became pregnant, voluntarily or involuntarily.

After serving a certain part of their sentence female convicts could apply for a ticket of leave. Like parole, this meant they were independent and free to earn a living, only having to report regularly to the police. When their sentence was nearly complete they could apply for a conditional pardon, the condition being that they could not return to Britain. When they had served their sentences, they were free by servitude.

It seems Susan was in trouble with the law on several occasions while being assigned. We must remember though, some masters were cruel and strict. Work placements for the women in particular very often involved dangerous environments such as the prospect of assault or rape. The homemade liquor that they drank at the time was unregulated, often adulterated with metho and other spirits, and often quite toxic.

Susan’s Convict Conduct Record (CON 40) details her colonial offences in which a couple of times she was sent to the ‘interior’ of the island which was supposed to protect well-behaved females from being corrupted by association with bad company and bad habits, such as drinking and prostitution, it isolated badly behaved women and was also a means of providing female servants to settlers in unappealing, isolated regions.

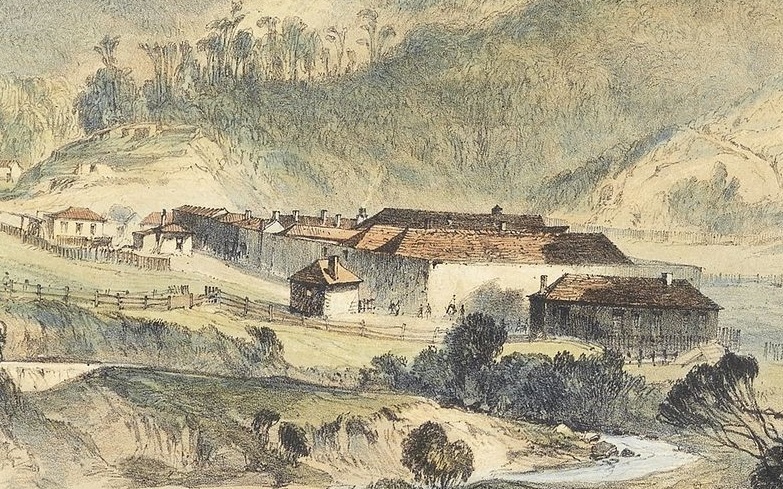

Significantly, in September 1838 she was found staying in the house of ‘a man called Yates’, where it seems she became pregnant (or was it earlier at her previous employment?) and as a punishment was then sent to the Cascades Female Factory in Hobart. It was an illegal offence to become pregnant while unmarried and on sentence (even if she had no control over the matter such as in the case of rape).

“The class system regulated both clothing and daily tasks of the women while in the factory. The first class (or more trustworthy) women were employed as cooks, task overseers and hospital attendants. Second class convicts were employed in making clothes for the establishment and preparing and mending linen. The crime class was sentenced to the washtub, laundering for the factory, the orphan school and the penitentiary; they also carded and spun wool. All of these tasks were subject to change at the discretion of the Principal Superintendent.

November to March saw unrelenting hours of labour, with the shorter days in winter being the only solace. With the sun not setting until after dinner for a large part of the year, the women were labouring up to 12 hours a day and even the slightest disobedience to the rules was punishable.” (Femalefactory.org.au)

Cascades Female Factory Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), hand coloured lithograph

He son James Mill (Mills) was born in the Cascades Female Factory in December 1838. (Mr Yates, in whose house she was found after absconding, could possibly be James’ biological father? A Mr H Yates was a carpenter and grocer in Macquarie Street, Hobart in the 1828 Tasmanian Almanack.)

Baby James was most likely kept with Susan, growing up in the Cascade Female Factory’s Nursery Yard, before being moved to the orphanage.

James was admitted to the Queens Orphanage at Newtown on 8 March 1841, aged 2 years and 3 months (originally placed with the girls), before being transferred to the boys section at the Kings Orphan School. (Library of Tasmania Archives SWD 7).

In 1841 she was then assigned to the home of Mr C Meredith in Swan Port (1841 Muster HO10).

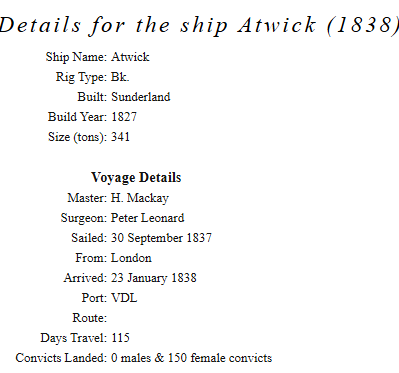

As we have seen previously Susan was charged with quite a few Colonial Offences which are recorded on her Convict Description List (CON 40). Here we find a little more detail –

- 3 Aug 1838, Master – Summerfield, Offence – Under the effects of liquor and insolence. Sentence – 3 days on bread and water in the cells and returned to government. (In 1838 Mr Summerfield had an eating house in Murray Street, Hobart. Susan may have been helping in the kitchen or laundry.

. - 14 Sep 1838, Master – Lovick – Offence – drunk and disorderly conduct in a house occupied by man of the name of Yates. Sentence – Crime Class, sent to interior, for 3 months then assigned on the other side of the Island. (Mr Thomas Lovick was publican at the Angel Inn, Argyle-street, Hobart in 1838, so was she working in the hotel?).

. - 22 Dec 1840 while in the service of Mr Fielding Brown, Davey Street, she absconded and was apprehended. (A death notice for a Mr Fielding Browne, barrister-at-law, Hobart Town appeared in the Launceston Examiner on 10 August 1871.)

. - 31 Dec 1840 – Master – Brown, Offence Absconding, existing sentence of absconding extended by six months, detained in the House of Correction before assigned. Decision 2 January 1841.

After obtained their Certificate of Freedom and serving out their sentence time, some women had no choice but to work as part time prostitutes to survive in the harsh economic climate. In fact in one convicts statement in 1842 “all the disorderly houses that receive absconded women are well known in the Convict Factory, and women are specifically directed to them”. Some women also teamed up with men they did not marry, gambling on their future survival.

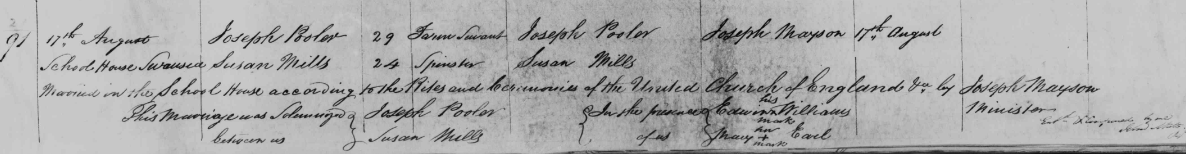

Susan married a convict named Joseph Pooler, a farm servant, born in Birmingham, England, (arrived Hobart aboard the ‘Clyde’ in 1830) on 17 August 1842 in the school house at Swansea, Avoca, Tasmania. Their Convict Application for Permission to Marry was dated 25 June 1842 in Hobart. The decision was approved. Surprisingly only 20 percent of Tasmanian male convicts married.

The witnesses to the Church of England marriage were Edwin Williams and Mary Earl. Both signed their names with a cross. (RGD37/1/3 no 91)

1842 Marriage Register, Swan Port, Avoca, Tasmania

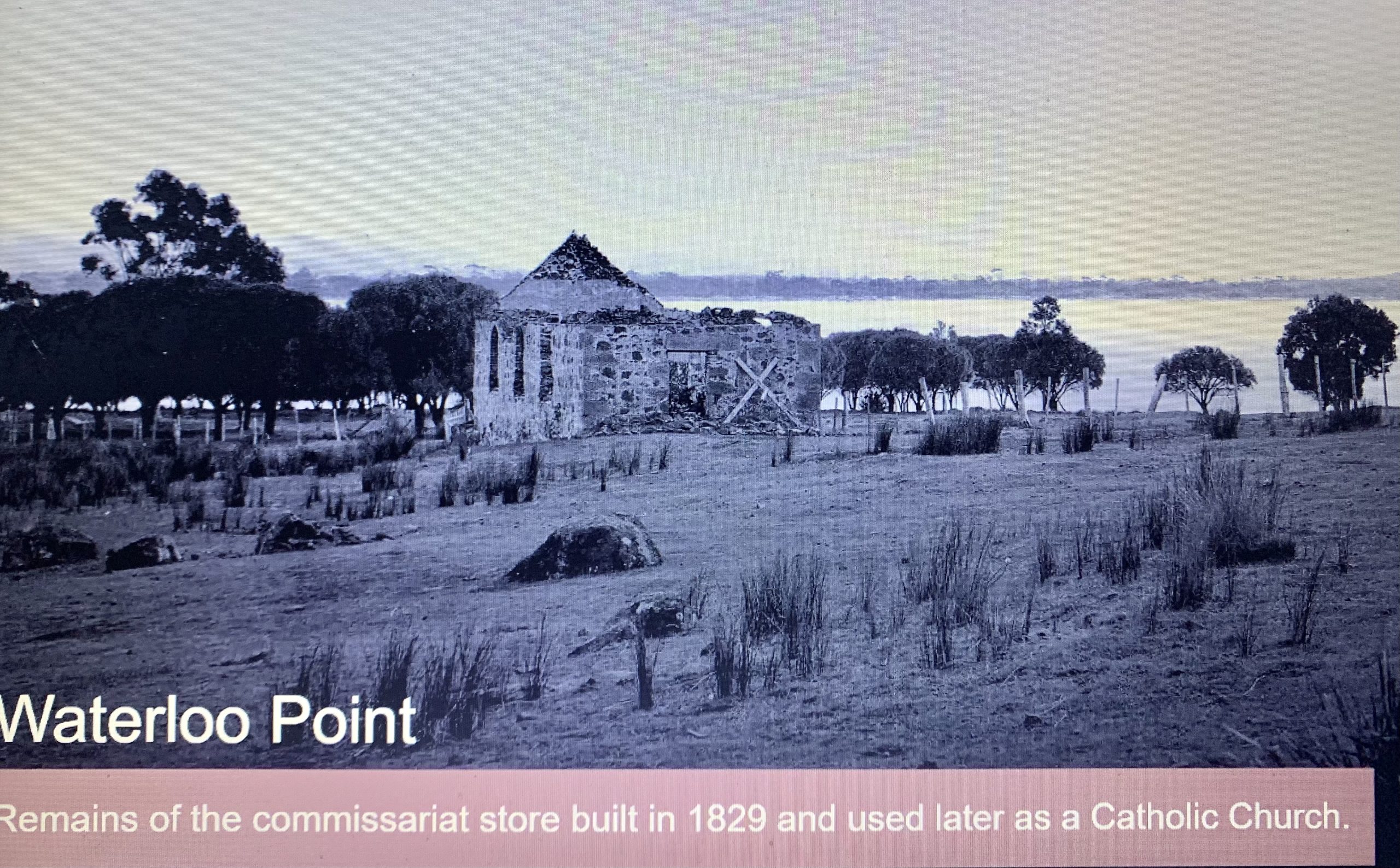

Joseph and Susan had a child together soon after their marriage – Joseph Edward Pooler on 10 November 1842 at Waterloo Point, Great Swan Port, Tasmania.

In January 1844 James was discharged from the orphanage and the records state he was ‘delivered to his mother’.

On 22 April 1844 at the age of 29 years, and after 7 years after her conviction in 1836 in Scotland, Susan was granted her convict Certificate of Freedom No 383. (CON 40).

Sadly a few years later when her son James Mills just was 10 years old Susan died in Hobart on 30 August 1849 at the age of just 34 years old (inflammation of the lungs). Her other son Joseph junior, by her husband Joseph, was just six. The family were residing at Murray Street in Hobart at the time of her death. She was stated to be a carpenters wife. (RGD35/1/2 no 2553).

Joseph Pooler, junior

At the age of 15 years, Joseph junior signed on as a member of the crew of the ship ‘Urania’ on 20 April 1858 in Hobart. Before departing the Port of Hobart, all ships’ captains and crew members were required to sign a pro forma document agreeing to not only the general nature and probable length of the voyage, but also to the specified regulations for preserving discipline on board. He appears in the Agreements between Masters of Vessels and Crews signed on at Hobart 1846 – Oct 1935 indexed by Colleen Read.

Several years later Joseph Pooler junior can also be found in the Victorian Government Gazette dated 26 January 1872, Mining Leases Declared Void at Enoch’s Point (near Woods Point via Alexandra, Victoria). His half brother James Mills was mining at Woods Point at the same time. Sometime between 1872 and 1876 Joseph junior travelled to Bushmans, nears Parkes, NSW where he can be found in the NSW Government Gazette in 1876. He married Martha Feldman in 1878 in Forbes and had five children, before dying in 1915 at Lake Cargelligo, NSW, where he is buried.

Joseph Pooler, James’ stepfather, also died of a lung disease at the age of 58 years on 29 May 1866 in Hobart (phthisis pulmonatis or TB).

Susan’s legacy

Sometimes survival in the new colony came down to a bit of luck, and the convicts own personality. Did Susan have a stubborn or rebellious nature, and did she endure difficult or abusive master and mistresses on her work placements? She did commit colonial offences such as absconding, but despite the harsh system which likely dehumanised her, after 7 years she gained her freedom, and had two surviving children which were both apparently healthy despite the extremely high mortality rate in the orphanage and colony, who went on to produce healthy families of their own.

It seems she married a decent man in Joseph Pooler, which was also a bit of pot luck in the new colony, as many women faced a life with a violent or irresponsible (drunk, gambler, deserter) husband. It seems they tried to work together for a better future, after their freedom was granted.

Sometime between 1849-1870 her two sons sailed to the Australian mainland, with James Mills settling in Alexandra, Victoria by 1870 and Joseph Edward Pooler marrying in Forbes, NSW in 1878 and then residing in Lake Cargelligo, NSW soon after.

James Henry Mills, son of Susanna Mill

We do know the two step-brothers kept in touch, and Joseph Pooler’s descendants had the same portrait photograph (pictured here) of James Mills handed down through their family, that was handed down in mine. They also had a birthday book with dates of James’ family in it.

Several DNA connections have been found between the descendants of Joseph Edward Pooler, and descendants of James Henry Mills, confirming they were indeed stepbrothers and descended from Susannah Mill, the convict from Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

So was Susan a victim of her times or her own poverty or just taken advantage of by others? Was she just a common criminal and petty thief, as the newspaper and trial reports would have us believe, or was she a young woman who had a legitimate husband, and two healthy children in Tasmania, and therefore the mother of a new generation that helped put the new colony on its feet. I for one, am glad to be descended from such an interesting, feisty and independent woman of her time.

Sources